COMMITTING TO CHARLESTON WITH CHARLESTON-STYLE GROWTH

A Case Study set in the historic district of Charleston, SC - prepared by Bevan & Liberatos

Charleston's dense, low-rise neighborhoods have a unique urban and architectural character that is so successful, so much in demand, that people pay top dollar to live there. In order to relieve gentrifying development pressure, to provide a more diverse housing stock for a wider range of incomes, to provide more diversity of commercial space, to provide more local jobs in the building trades, and to meet the growing demand for Charleston's charming streets, new development should follow Charleston's authentic urban and architectural patterns. In other words, instead of building Anyplace, USA, Charleston should be building more of Charleston. Low-rise Charleston-style urbanism can match the densities of high-rise, wide-street developments; it is more commercially viable in the long term; it is more environmentally sustainable; it discourages sprawl; it is diverse, authentically local, and aesthetically beautiful.

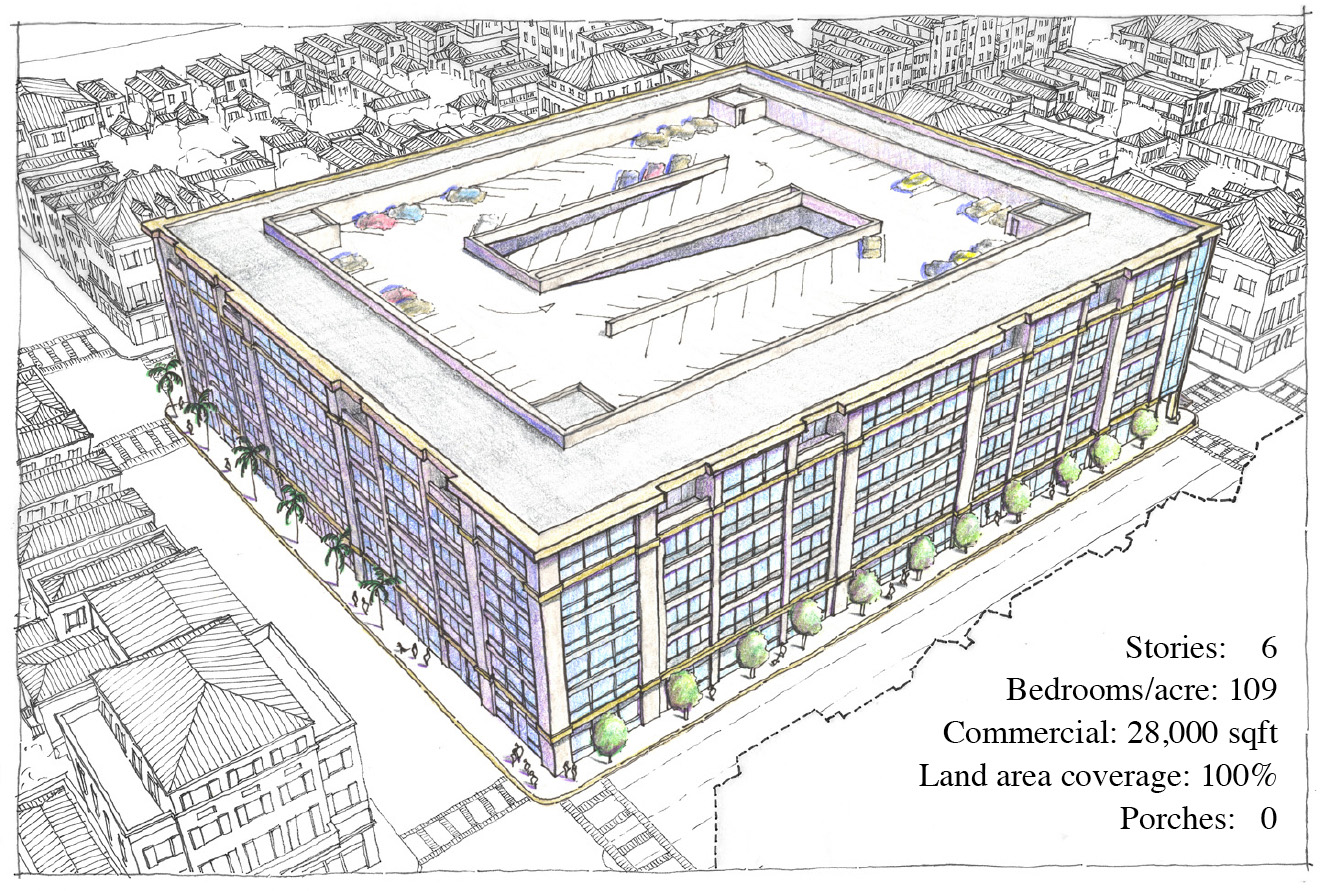

The images above show that it takes 6 stories of Texas-donut to accommodate the same number of bedrooms, and the same amount of retail space, as Charleston-style urbanism can in only 2-4 stories - which it does while also accommodating porches, gardens, rooms with multiple exposures, parking, and a diversity of housing and building types. The most charming places in peninsular Charleston are also the densest. It is, therefore, not the proposed densities of new projects that is incompatible with the neighborhoods, it is the proposed form in which it takes. There is room in Charleston for more density, but only if it is well-designed density.

Texas-donut density vs. Charleston-style density (residential only)

(Commonly found in Charlestowne, Harleston, Ansonborough, Radcliffborough, Canonborough, Elliotborough, Eastside, Westside, and N. Central.)

6 stories

192 bedrooms

109 bedrms/acre

672 cars

3 entrances

0 gardens

0 porches

24 rooms with 2 exposures*

2-3 stories

194 bedrooms

108 bedrms/acre

110 cars

258 entrances

17 gardens

72 porches

432 rooms with 2+ exposures*

*A room's "exposures" are the number of walls of a room that have a window. In hot and humid climates, good rooms have at least 2 exposures to take advantage of breezes.

Texas-donut density vs. Charleston-style density (mixed-use)

(Commonly found on arterial streets, such as East Bay, Broad, Calhoun, King, and Meeting Streets.)

6 stories

27,500 sqft ground-floor commercial (shown in red)

165 bedrooms

165 residential units

0 gardens

0 porches

2-4 stories

28,000 sqft ground-floor commercial (shown in red)

185 bedrooms

120 residential units

13 gardens

68 porches

CHARLESTON'S URBANISM, A MODEL FOR SUSTAINABLE GROWTH

Charleston is home to one of architecture's unique contributions: the Charleston single-house. What is less known is that Charleston is also home to one of urbanism's unique contributions: side-yard urbanism. Although this type of urbanism works well with single-houses, it is not dependent on them, and it is used throughout Charleston even where there are no single-houses. It is characterized by clearly defined public streets and squares, deep lots, and the locating of the buildings, which are kept narrow to catch the breeze, on the side of the lot, creating gaps between buildings on successive lots. It is an ingenious solution to achieving an urban level of density that is yet livable in a hot, humid, sub-tropical climate. Charleston's blocks are highly permeable, diverse, and granular. Compared to the globally ubiquitous Texas-donut, Charleston-style urbanism is more...

DIVERSE

The Texas-donut offers only one type of housing and one type of retail, resulting in an area of monoculture. Charleston's urbanism is defined by a diversity of building types in varying sizes that are flexible, adaptable, and able to respond to changing markets. Charleston's urbanism accommodates single-family homes, duplexes, tenements, apartment houses, offices, inns, hotels, shops, corner stores, grocers, restaurants, bars, cafes, schools, churches, libraries, and institutions that enrich the urban experience and provide a diversity of job opportunities for a diverse citizenry. The best way to achieve this is through incremental development.

LIVABLE

Charleston has a hot, humid, sub-tropical climate. Urbanism that accommodates shading porches and loggias, gardens, and courts, is more livable than urbanism that fills in the entire block. Charleston's urban character is defined by blocks that are highly permeable. This allows buildings to take advantage of breezes and rooms to have windows on multiple exposures. While dense, Charleston's urbanism balances first-rate private space with a first-rate public realm in the form of clearly defined streets, many of which are veritable linear parks.

WALKABLE

Charleston-style urbanism is characterized by an interconnected network of varied street-types which reduces congestion, increases safety, and provides a structure for multi-modal transit. It has also been mixed-use since 1670, and the infrastructure to get everything one needs for daily life within walking distance is there. Charleston's urbanism is characterized by narrow fronts, which puts more people onto the street than do block-sized buildings with entrances from behind.

SUSTAINABLE

Local patterns of urbanism and architecture contain within them a wealth of information on climatically-appropriate design and construction. Charleston-style urbanism responds to the conditions of the site, incorporating both old solutions, and recent lessons on building in balance with nature. The Texas-donut model varies very little from place to place, or even from its north face to its south.

VALUABLE

By investing in the infrastructure that makes new development possible, the city and its citizens have a financial stake in the long-term value of new developments. The return on investment for Charleston-style urbanism is greater, and longer-lasting, than urban patterns based on short-term profit models.

CASE STUDY

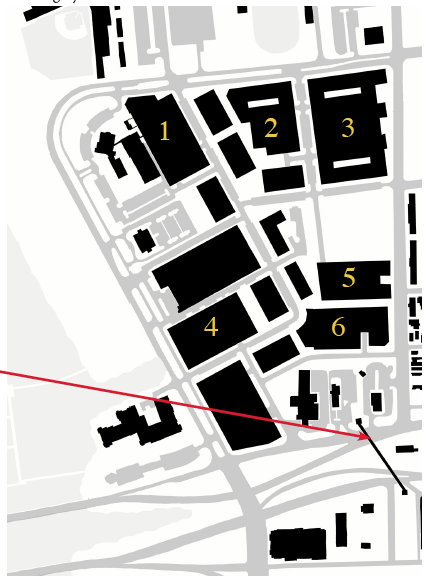

The WestEdge project (previously called the Horizon District Development) is being planned by the City of Charleston and a private foundation. This study asks, instead of a neighborhood of Texas-donuts, what if Charleston-style urbanism were extended to the Ashley River?

CASE STUDY SITE:

Situated along the shore of the Ashley River, the proposed new WestEdge project is one of three major developments currently being planned for peninsular Charleston. The site is the size of a neighborhood - about a 10 minute walk end-to-end. It is bounded to the north by Fishburne Street with the Joe Riley Ballpark and Burke High School, to the east by the historic Westside Neighborhood including Gadsden's Green, to the south by the Crosstown Expressway (also known as highway-17), and to the west by Brittlebank Park and the Bristol condominium building. Previously the location of a municipal trash dump, this long-neglected site is comparable in size to the original walled city of Charleston.

Current proposal:

Charleston-style proposal:

-Wide streets with limited connectivity

-Mega-blocks

-Car-centric planning, including 6 new parking garages

-cuts off adjacent Westside neighborhood from waterfront

-Block-sized buildings

-Climatically inappropriate, disposable buildings

-No local ownership opportunities

-Culvert and fill Gadsen's Creek

-Network of diverse, interconnected streets

-Small blocks

-Multi-modal transit opportunities

-Connects adjacent neighborhood to waterfront

-Flexible and adaptable buildings

-Climatically appropriate, maintain-able, repairable, durable buildings

-Promotes sustainable local economies

-Utilize Gadsen's Creek as amenity

A plan that would allow incremental, Charleston-style growth, following the urban and architectural patterns that give Charleston its unique character, employing more builders, creating a more valuable tax base.

On Street-types:

Congestion and traffic cannot be reduced by making streets wider, but it can be mitigated by providing numerous and varied alternative routes. Dead-end, L-shaped, and too-wide streets - like those in the WestEdge proposal - make congestion worse, and are unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists. The gridded streets of Charleston's historic district - though narrower than suburban arterial highways - are sufficiently wide for modern use, and have numerous advantages over wider ones. New streets in the historic district should should follow the Charleston model, not a sub-urban one.

On Parking and Transportation:

“There needs to be an understanding that the more parking that gets built, the more congestion will be created.”

- Gabe Klien, Transportation and Mobility Study for the City of Charleston

By creating a streets and sidewalks that are safe for pedestrians and comfortable for cyclists, many trips can be made without a car. Multi-modal transit includes walking, biking, driving, and buses or trams linked to regional train stations and airports. When systems are well-designed, many trips are easier, quicker, and more convenient by public transit than in a personal car. Low-income residents should be able to rely on walking, biking and public transportation for 100% of their trips, relieving them of the cost of owning, maintaining, and insuring a car. Charleston's urbanism, which provides parking not just on the street, but also between buildings, accommodates more parking than most other types of urbanism. Limiting parking to residential and local use is encourages tourists and commuters to take public transportation.

The current WestEdge proposal, on the other hand, has streets that are too wide, monotonous blocks that are too long, would make for an uncomfortable and dangerous experience for pedestrians and drivers alike. This kind of street-scape would further disconnect the Westside neighborhood from the waterfront. Its car-centric approach to transportation includes 6 new parking garages, bringing the total for the neighborhood to seven. Parking garages are expensive to build - so expensive that Charleston has created a TIF (Tax Incremental Financing) district to help pay for them. Estimates for the cost of the garages come to around $30,000 per space. With 6 parking garages slated and an average of about 1,200 spaces per garage, the infrastructure just for these garages could amount to more than $36,000,000 in public funds. These are funds that, if Charleston were taking the long-term view, could be put towards the public transportation system.

On Waterways:

One of the last remaining salvageable tidal creeks on the Peninsula, Gasden's Creek has long been neglected. Rather than rehabilitate the valuable wetlands, the current WestEdge proposal is to put the creek into a culvert and build on top of it. Charleston Waterkeeper, Delete Apathy, and other community members are fighting to preserve the creek. By maintaining the creek, the community would be enhanced in three distinct ways: 1) it would provide a Colonial Lake-like recreational amenity, 2) it would mitigate flooding, and 3) it would help filter water runoff before it gets to the Ashley River.

Existing Conditions:

WestEdge Proposal:

Civic Conservation Study:

On Building Sustainably:

Charleston's architecture has a modest window-to-wall ratio, not because it couldn't be otherwise, but because in this climate it makes sense. Glass building facades, like the ones proposed for the WestEdge district, are climatically inappropriate for the hot, humid, subtropical Lowcountry and are inefficient both from an operational and and embodied energy standpoint. There are also many other sustainable solutions found in Charleston's older buildings - thermal mass, shading porches and loggias, water-shedding moldings, pitched roofs, openable windows, protecting shutters - that should be utilized to reduce demand on mechanical heating and cooling systems and to prolong the lives of buildings.

Curtain wall construction - be it wrapped with a Modernist or Traditional styled "skin" - condemns a building to a mere 30-40 year lifespan. This not only fills our landfills with unnecessary waste (hundreds of millions of tons of building waste are sent to our landfills every year), it also robs us of the opportunity to physically link generations through a shared architecture, and fails to provide communities with a sense of rootedness and connection to place. (For more on this, see Our Disposable Architecture .)

More at: www.westedgecharleston.com/

On Building Adaptability:

Small buildings are more adaptable for reuse as requirements change over time. Flexible building stock are essential for encouraging small businesses, local start-ups, and an entrepreneurial spirit in a community. Below are two examples of tech companies - one small, one large - that operate out of buildings built in the 1800's in Charleston's historic district.

On the local economy:

WestEdge Proposal:

Civic Conservation Study:

On Social, Environmental, and Economic Sustainability:

It is easy to get excited about the prospect of the financial infusion that new development promises, but what if the financial benefit could be even greater, and more long-lasting? There are a few ways to assess the financial flow of a new development, first is the question of where and how the profit from construction is dispersed. Will the money invested remain to cycle in the local economy? Will the building program strengthen the local building trades, will there be work for the contractors and handymen whose kids attend the nearby school? How much is the city investing in the infrastructure for the project, and will there be a return on that investment? Then, when the construction project is through, who will own the buildings? Where will rents be paid? Will there be opportunities for low-income home ownership? Will the new neighborhood give a boost to the local school, or drain resources from it? Will the new buildings house local businesses? How will those businesses invest in the local community? New plans for development should be judged by how well these questions are answered.

On Land-use:

The value of the properties in Charleston's historic district outpaces others in the area considerably. It was mentioned above that the site of the WestEdge development is about the same size as the original walled city, about 50 or 60 acres. Today, that area is thriving and is home to about 720 residences (including single family detached, rowhouses, stacked condo flats, duplexes and triplexes, apartments, carriage houses and dependencies), about 789,000 sqft. of commercial space (including food stores, 3 inns, 5 banks, 11 restaurants, 26 art galleries, and various other small businesses), and great civic and institutional buildings (6 museums, 5 churches, 6 cemeteries, 2 arts theaters, Charleston's city hall, and a 450-student school). This dense diversity creates not only a charming and livable neighborhood, it provides significant revenue to the city. Since the value per acre is higher, the taxes paid per acre are higher, and yet the infrastructure and services required are lower. The efficient planning of the area requires fewer miles of roadways, and water and sewage lines per person, while trash and recycling services are vastly more efficient, and therefore cost-effective, than more widely dispersed (off-peninsula) areas of the city.

On Gentrification:

The demand for the charm of Charleston-style urbanism is growing, but the supply is not. Long-time residents are finding it unaffordable to live in the place they know as home. Cities change, and there is little one can do to stop gentrification trends, but the simple act of making more of what is in demand may be enough to take pressure off of existing neighborhoods and communities. The only viable solution to relieve the demand for Charleston is to make more of Charleston.

Historic Districts are sometimes accused of being the generator of gentrification because low-income residents cannot afford to upkeep their home to the standards of a board of architecture review - this argument is based on a valid point: there may be cheaper alternatives than proper care of an historic house or building. However, the solution isn't to lower the standards, but to bolster the local building economy by promoting participation in it, by supporting local craftsmen, and by finding financial support for neighbors who need it.

On Regional Planning:

The Texas-donut is not a bad building type, per se; it was a tool developed by New Urbanists to help revitalize dead and dying midwestern downtowns by housing people who want to move back to the city in the absence of public transportation. But Charleston's historic district isn't dead or dying - it's thriving! So much so that it is becoming unaffordable. But that doesn't mean there might not be other places in the city that would benefit from such an injection of density. Citadel Mall, built in 1981 and recently foreclosed, is preparing redevelopment plans as part of the city's West Ashley Strategic Plan. Near the intersection of I-17 and I-526, about 5 1/2 miles from downtown Charleston, it is an excellent place for a mixed-use town center. MUSC's peninsular campus could be connected to new medical offices by a public transit line.

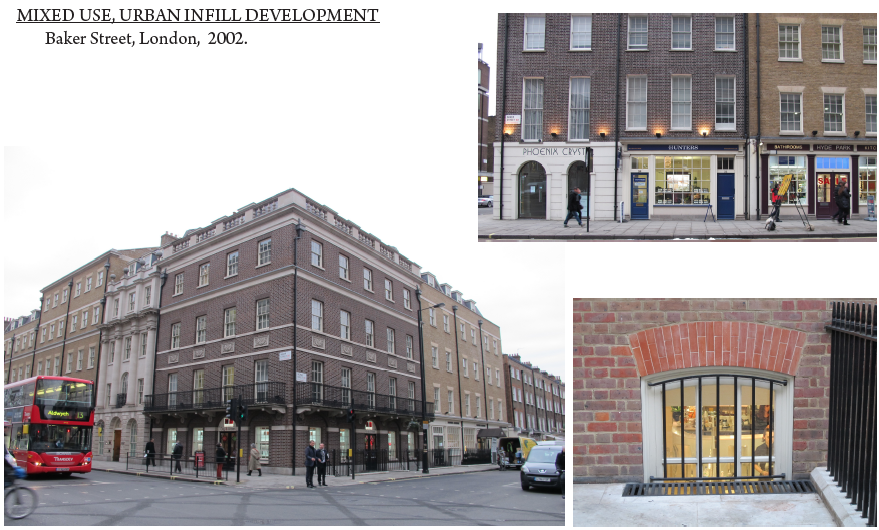

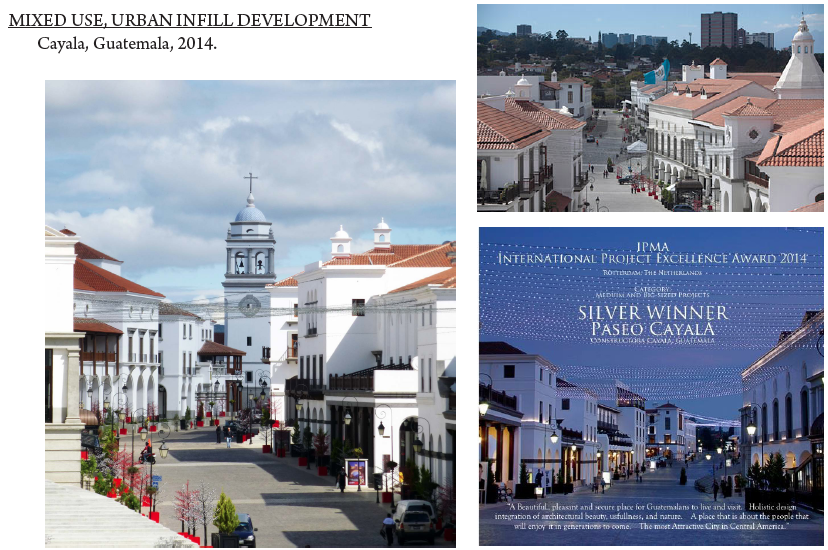

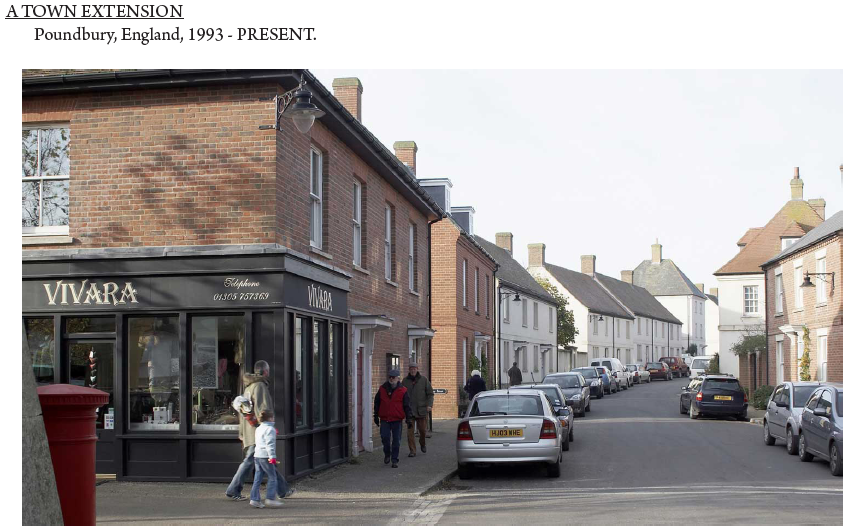

Examples of similar projects elsewhere:

Solutions like this case study are not just hypothetical: new developments that follow local patterns of architecture and urbanism are being built all around the world with great success. Below are images from four recent projects: Baker Street in London; Cayala adjacent to Guatemala City; a project outside of Paris; and Poundbury, an extension to the town of Dorchester, England. The main criticism these projects receive is that - because they are in such high demand - even if their prices begin low, they quickly become too expensive for the great diversity needed for a sustainable city. The only solution to that problem is to build more like them.